In the documentary The Eternal Children (see also ‘CocoRosie’), Antony Hegarty, lead singer of the pop ensemble Antony and the Johnsons, perceives the waning of a postmodern sensibility, and the rise of something else.

I think this is a more wake period in culture. That was a horrible period. You know, the early nineties, you had like Kurt Cobain. The only thing that could manage to break through that wall was this scream of depression and rage that was Kurt Cobain. But other than that, what was there? Things sort of radically diversified after the new millennium. […] Suddenly, there was this frolicking group of outrageously colourful young people with their eyes wide open. But not like naïve, but almost emerging from a basic need to survive and to live… […] There was something very primary and very beautiful about what they were doing, and creating spaces that had the potential for hope to exist in them. […] It’s not cynical, that’s the thing.

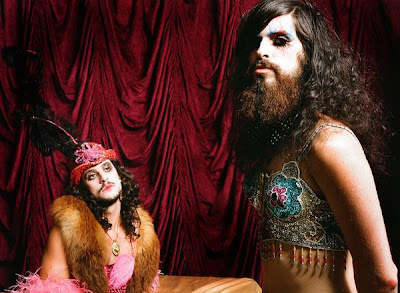

Indeed, something has drastically changed since the beginning of the new millennium. Something, or someone, managed to break through ‘that wall’ – without screaming or raging (as grunge did in the early nineties), or without becoming apathetic (as punk did in the late seventies and eighties). During the past decade a generation emerged that does not turn to anger or defeatism, but instead seeks to create alternate spaces for hope and desire. This generation reflects a cultural shift, a shift from a period of cynicism towards a more ‘wake period’, as Antony tends to describe it. I am talking, of course, about the latest folk revival in western history mostly referred to as free-, NU- or freak folk. A musical genre that is exemplary the rising of the New Weird Generation and (it’s) New Romanticism.

Antony wasn’t the only one though sensing the end of postmodernism in popular music. As early as 2003, Scottish music journalist David Keenan prophesised the emergence of a generation that no longer shares the postmodern attitude. In an article on a two-day music festival held at a cotton mill in the wooded area of Brattleboro, Vermont – the Brattleboro Free Folk Fest – Keenan introduced his readers to the rise of the New Weird America: ‘a groundswell musical movement rising out of the USA’s backwoods [l]oosely called free folk’. With the term New Weird America he referred to the making of a counter culture in the early sixties of the 20th century, when among artists such as Bob Dylan (and The Band), John Fahey and Joan Baez there was a communal counter movement that occurred in reaction to the Vietnam war and excessive capitalism. Just as in Brattleboro, the heart of this counter culture was formed by folk music inspired by the American ‘hillbilly’ and ‘blues’ tradition once recorded by ethnomusicologist and mystic Harry Smith on his still legendary album An Anthology Of American Folk Music. In Invisible Republic (1998) music journalist Greil Marcus called this tradition Old, Weird America.

So, what is New Weird America?

Whoever glances at the programme booklet of the Free Folk Fest will see that the names of Devendra Banhart, CocoRosie, Joanna Newsom, Akron/Family, and Antony & the Johnsons are missing. While these very artists are now called the standard-bearers of the genre, more obscure acts were listed such as the extremely rhythmic, psychedelic freak rock of Sunburned Hand Of The Man, the minimalism of the Charalambides, and the acid folk of Six Organs Of Admittance, among others. The Brattleboro festival nonetheless should be called the cradle of free folk, mainly because many of the artists present at the festival were selected a year later by Devendra Banhart for his limited edition album The Golden Apples Of The Sun, an album he put together at the request of the American art magazine Arthur. On this album, as well as music by direct friends such as the already mentioned CocoRosie, Joanna Newsom and Antony Hegarty, Banhart also selected the music of Jack Rose and Matt Valentine – two key figures at Brattleboro. Matt Valentine of the band Tower Recordings even was the one who co-organized it. The Free Folk Fest, in other words, already contained the binding elements of the otherwise miscellaneous musicians on Banhart’s compilation album. As different as they might be, they belong to the same musical family.

What then are these binding elements? One important characteristic of free folk is the merging of genres. Listen to The Golden Apples Of The Sun and you will hear psychedelic rock, acoustic folk, opera, metal, hip hop, free jazz, noise, tropicália, country, blues, funk, soul, drone, and much more. This mixing of music in New Weird America is used as a way to provoke enthusiasm and empathy, as well as renewed sources of inspiration, commitment, and meaning. Free folk musicians want to jack into the musical cosmos of the past in order to push the boundaries between genres and to create something unique and authentic. The two main features of free folk concerts, moreover, are improvisation (the constant switching of styles on stage) and the application of the drone (the constant, almost hypnotic repetition of a chord or note it). According to most of the musicians present at Brattleboro, it was all about becoming immersed in the crowd, the instruments, the music. John Moloney, front man of Sunburned Hand Of The Man, dictates the following in David Keenan’s article:

“There always is a loose plan that goes right out the window the second we plug in. Always. Like in Brattleboro, the music just took control, the sounds, the power. I feel like we conjure up the sounds from the beyond or from right next door. I honestly feel like we are some sort of channelling device or medium. Not some New Age bullshit but some sort of conscious coincidence. It’s a real uplifting experience and we are proud to be the ones to make everyone smile and come out of themselves a little.”

Indeed, the free folk concerts I visited (especially the Akron/Family-concert at the 2007 Motel Mozaique festival) had this exact same vibe. Performers were constantly getting off-stage and handing out instruments and children’s toys to some of the most enthusiast spectators, sharing the same musical experience with them in order to construct some sort of carnivalesque fest. Indeed, this stage performance was something quite different from most of the punk and grunge performances in the eighties and early nineties, when instruments and sound systems were being destroyed and musicians were spitting at their audiences.

The desire of immersing in the music and the crowd is very Romantic. One can for example think of Nietzsche’s description of Dionysian ecstasy or his enthusiasm for Wagner’s Gesamtkunst. It is the desire of the Romantic to return to an authentic state of being – that of the tragic Greek, the free playing child and, of course, the ‘return to nature’.

Performing improvisational music ‘to get folks moving’ isn’t the only Romantic characteristic of free folk though. In free folk, the Romantic quest for authenticity is omnipresent. In the first place, it is for example why New Weird America is into folk music rather than being into techno. As Keenan describes it, Folk music is one of the most ‘original and ancient of all human expressions’. It is why the Brattleboro Free Folk Fest took place in a cotton mill in the wooded area of Vermont, just outside of the big cities of Boston and New York, although most of the musicians were, and still are, city-based – because ‘the music doesn’t sound right when you are not harmonious with nature’. It is why free folk concerts are like small social events, why the scene feels like a musical family, and why some of the musicians are living in communes (Akron/Family, CocoRosie). It is why acoustic instruments such as the harp, the banjo, the mandolin, and the guitar are most frequently used. As Ben Chasny, front man of Six Organs Of Admittance explains, ‘because it is a less mediated form of expression than electric music’. It is also why children’s toys are so often used as instruments, why artists like Bianca ‘Coco’ Cassady and Joanna Newsom sing in a voice that hovers between that of Björk and a toddler, and why Devandra Banhart is so often singing about behaving as a little child although facing the inevitable process of becoming older (listen to e.g. the sonds “Longhaired Child”, “I Feel Just Like A Child”, “Chinese Children” and “Little Boys”, all on his third album Cripple Crow). It is why free folk musicians sing about living in a dreamlike world of elves and fairies, and why they share a desire for spiriting nature again. Consider, for example, the Akron/Family song “River”, or the songs on the latest Antony and the Johnson’s album The Crying Light. It’s because the everyday is regarded as too rational, mature, artificial, technological, et cetera – and, in the famous words of Novalis, ‘must be romanticised’ again. The world must be authentic again in a way nature, the child’s imagination, and ancient folk music are regarded or constructed as being authentic.

Would this be considered Freak Folk?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zV5eWwAmOGI

Pingback: The Beatles: Unplugged Collects Acoustic Demos of White Album Songs (1968) | Open Culture